Language, even before it is spoken, is necessary in order to think.

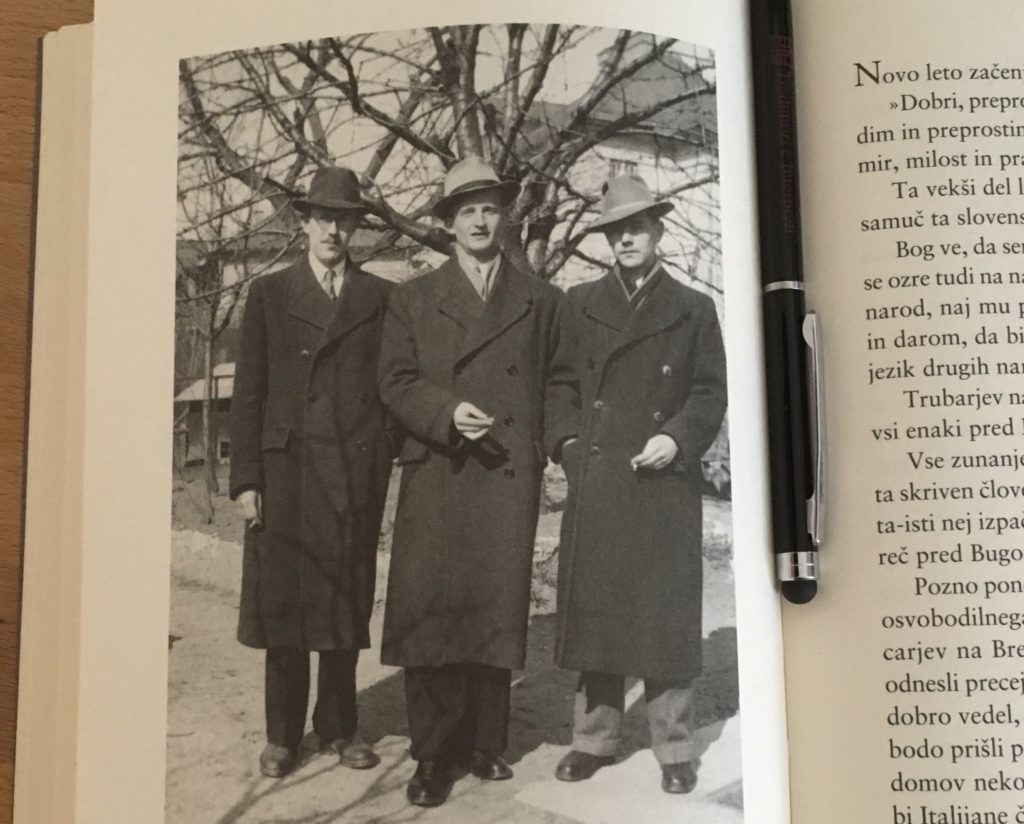

I recently read a diary written in the decade between 1937 and 1947 by Slovenian theatre director and writer Mirko Mahnič. At that time, the young author, who in 1939 was 20 years old, was extremely distressed by the tragic division of the Slovenian people during the Second World War. One part of the nation chose the armed revolt against Nazi-Fascism, a partisan struggle that was soon monopolized and exploited by the Communist Party. Others, on the contrary, feared communism more than Nazism and so chose to ally with the invaders against the partisans commanded by Tito.

Mahnič suffered because of the atrocities perpetrated by both conflicting parties, while at the same time having a clear perception that in the context of global war the survival of the Slovenian people was already threatened because of its small size. The fratricidal conflict therefore appeared even more absurd to him and consequently he developed in those years a clear awareness: that language was the most important treasure the small Slovenian nation had to safeguard in order to survive – language understood as the ability to think freely, to express one’s ideas clearly, to discuss matters through frank exchange while respecting different opinions, the ability to seek and find shared goals and ways towards a future of hope, despite the constant threat from the country’s larger and more powerful neighbours.

After the war, when Mahnič worked as a professor of Slovenian language in a secondary school, he noticed on the one hand a strong desire of his students to learn the language well in order to be able to express themselves clearly, with freedom and frankness, looking for the truth behind things. On the other hand, however, his work clashed with the ideological propaganda of the new communist authorities who reacted with hostility, falsehood, arrogance and brutality to any thought other than the one officially promoted, demanding self-censorship and pushing for a distorted and deceitful use of language.

Nowadays, threats are different. Slovenia is an independent and democratic state and a nation proud of its economic, technological and cultural progress.

But while reading Mahnič’s diary, I realized that the task of cultivating and enriching one’s own language remains today just as urgent, if not even more so, by saying what one really thinks, speaking clearly, facing each other in frank and honest debate, writing and publishing valuable texts, promoting good quality translations etc.

I think this commitment is necessary to combat various contemporary forms of language abuse, for example the one that sees language as just a means of selling something. Or the sort of abuse often committed by politicians, pronouncing nebulous phrases in order to avoid the real issues and not to have to give clear answers, to beguile potential voters etc. In this regard, I can also think of misuse by various websites in virtually all languages, their texts resulting from machine translation without any professional editing and therefore full of embarrassing errors and absurdities…

I’d like to conclude this reflection with a few words from the ethical code of the Italian Association of Translators and Interpreters, claiming that translator’s activities shall be “carried out in the interests of peace, security, justice, health, well-being and the economic, scientific and cultural development of peoples”.