by Tone Dolgan | Sep 17, 2019 | On Language and Translation

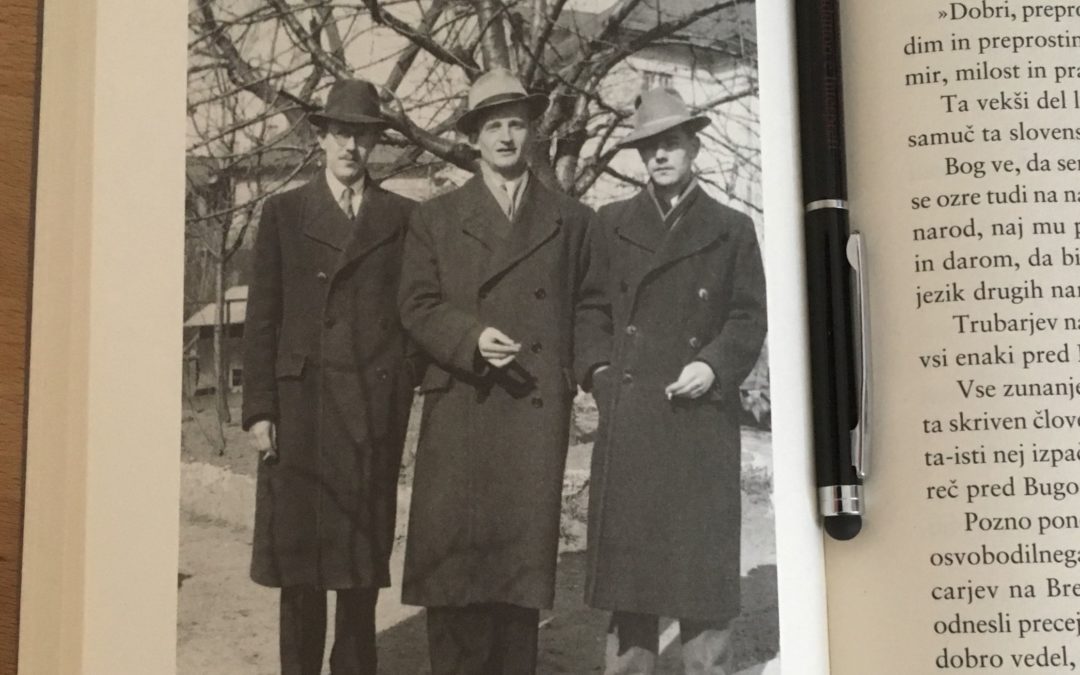

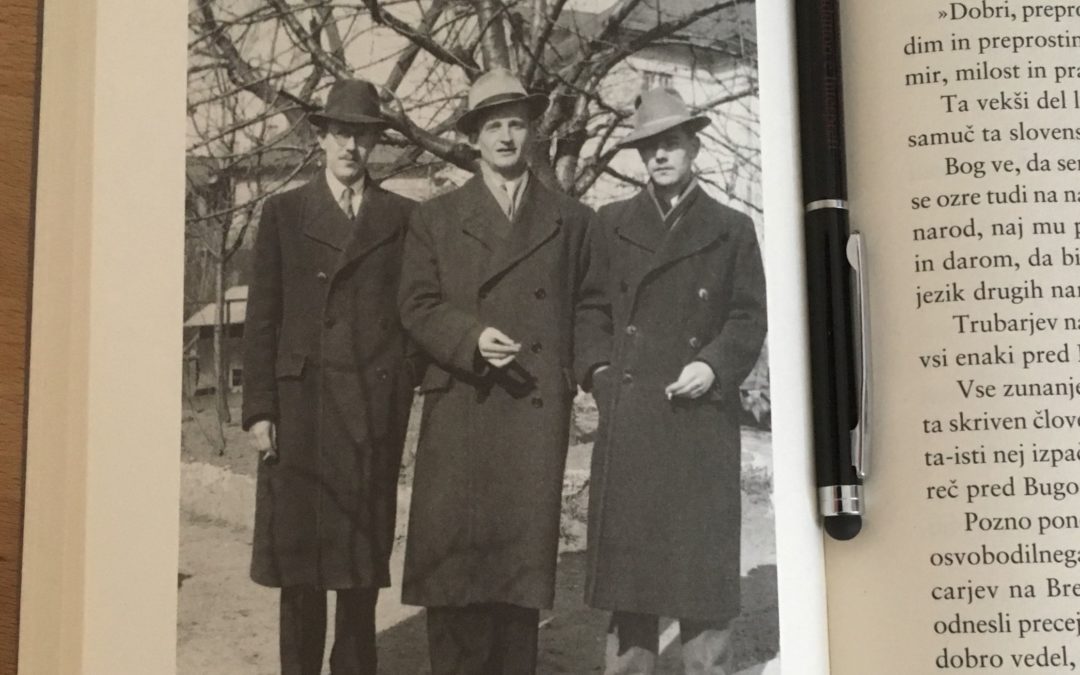

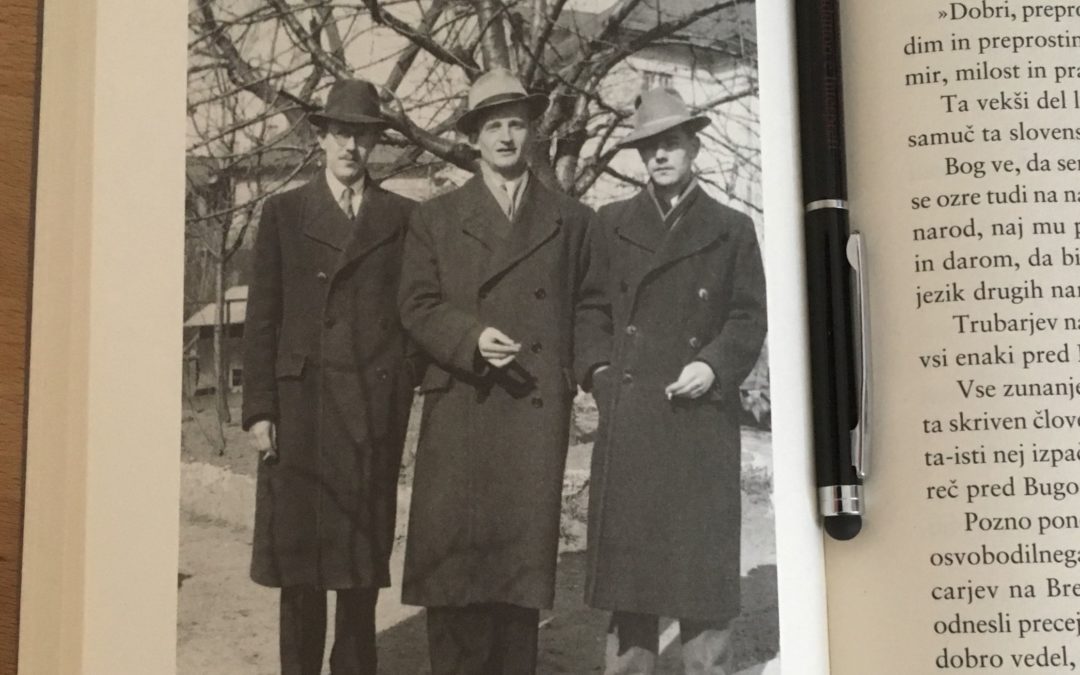

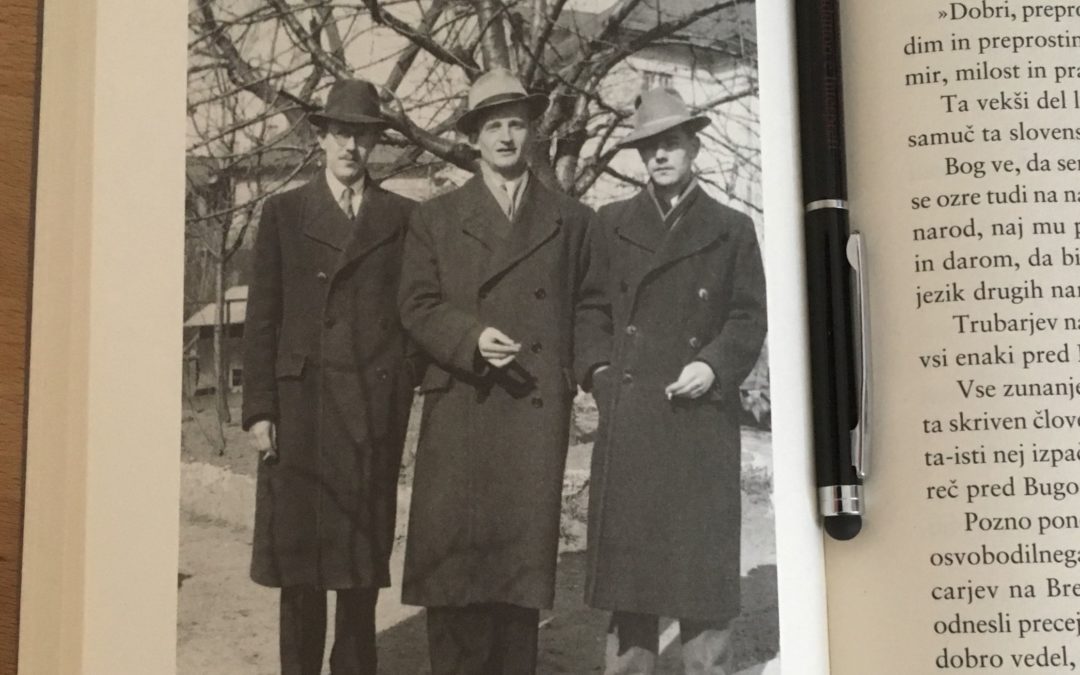

Language, even before it is spoken, is necessary in order to think. I recently read a diary written in the decade between 1937 and 1947 by Slovenian theatre director and writer Mirko Mahnič. At that time, the young author, who in 1939 was 20 years old, was extremely distressed by the tragic division of the Slovenian people during the Second World War. One part of the nation chose the armed revolt against Nazi-Fascism, a partisan struggle that was soon monopolized and exploited by the Communist Party. Others, on the contrary, feared communism more than Nazism and so chose to ally with the invaders against the partisans commanded by Tito. Mahnič suffered because of the atrocities perpetrated by both conflicting parties, while at the same time having a clear perception that in the context of global war the survival of the Slovenian people was already threatened because of its small size. The fratricidal conflict therefore appeared even more absurd to him and consequently he developed in those years a clear awareness: that language was the most important treasure the small Slovenian nation had to safeguard in order to survive – language understood as the ability to think freely, to express one’s ideas clearly, to discuss matters through frank exchange while respecting different opinions, the ability to seek and find shared goals and ways towards a future of hope, despite the constant threat from the country’s larger and more powerful neighbours. After the war, when Mahnič worked as a professor of Slovenian language in a secondary school, he noticed on the one hand a strong desire of his students to learn...